Few things are as such iconic symbols of "vikingness" as battle-axes, and the bigger the better. Leaving aside all sorts of fantasy designs, the historical version of this iconic weapon is the big, bad, broad-axe, also known as the breið-öx in Old Norse, the Dane-axe (for its Scandinavian origin, as experienced painfully by Anglo-Saxons), or the large variant of the Type M axe (for the Petersen typology aficionados) - I'll use the term Dane-axe from here on to keep things simple.

In almost all respect, our knowledge about it lives up to our modern (cliché) expectations of the fearsome battle-axe: a very large blade with sharp edge and horns, wielded in two hands by elite warriors... Several surviving axes further confirm their elite status by the presence of decorative inlays in silver or gold on the axe-head.

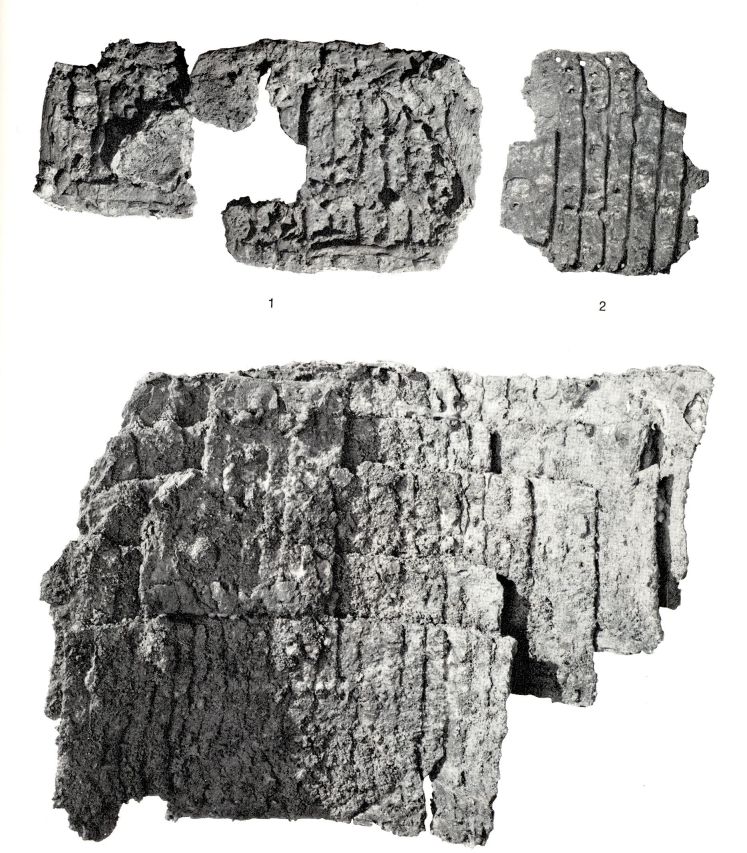

Among the numerous finds of such Dane-axes of various sizes and shapes, there is a specific category that emerges: the axes with a collar made of a sheet of copper-alloy (brass or bronze) inserted between the axe-head and the shaft. The archetype of such axes is the axe from Langeid, one of the best-known (and largest) Dane-axes. A few axes with collars of different types have been found (in particular a number of small bearded axes from Gotland), but in general the copper-alloy collar is very much a Dane-axe thing - you can find a catalogue of such axes here.

|

|

|

| The iconic (and massive) axe from Langeid, Norway, alongside its replica, a similar axe found in London, England, and a different design of collar on an axe from Bjorå, Norway. | ||

The purpose of such collars is dual, and quite obvious to figure out. First, the purpose is of course decoration of the haft (in addition, or rather in substitution as we'll see, to the inlaying of the axehead). And second, the purpose is reinforcement of the shaft: we know that having the head of a Dane-axe flying off its haft is a plausible thing (according to the Bayeux tapestry); additionally, the Dane-axe can be seen as a predecessor of later medieval cut-and-thrust pole-weapons such as bills and halberds, which often had their head attached to the haft by the means of long langets - strips of iron meant to protect the the haft from breaking just below the head, because that is the part of the haft which takes the most stress when striking with the weapon, and also the part which is the most likely to be damaged by the enemy's weapons.

|

|

| This is what langets are on a halberd head. | And this is why they are useful. |

Because the presence non-ferrous metal helps with the archaeological survival of perishable materials such as wood, these Dane-axes with collars very often have the part of the shaft inside the collar preserved in good shape. This is a tremendous source of knowledge about the shafts of Norse axes, but it also raises a serious question:

How does the head of such a collared Dane-axe even hold on its haft? (and why is that even a question?)

Let's take it slowly.

To be usable, an axe needs to have its head attached to the haft robustly enough that the head doesn't fly off when it is subjected to the centrifugal force of a swing with the axe, or when the axe is shaken by an impact. Independently from the shape of shaft and wood species used in various axe traditions, there are fundamentally two ways of hafting a typical axe: hafting from above, and hafting from below using a wedge.

The Norse tradition was very definitely to haft from below using a wedge, which makes even more sense for a large two-handed axe, which has more than enough weight at the top and would benefit from a solid grip provided by a flared bottom of the haft. However, the collared Dane-axes have no wedge.

No. Wedge.

OK, technically there is one example with a large nail in the eye of the axe serving the purpose of a wedge, and one shaft has a crack which might be the slit were a lost wedge was once inserted. But in most cases, no wedge, and a hafting from below. How can that possibly work?

Gluing? Nope - even with modern chemistry gluing metal on metal is far from easy, and no one in their right mind would use an axe the head of which has merely been glued to a polished haft.

Wedging with the brass collar itself? Hm, maybe, but not really. Some collars are indeed made of several parts, some of which look like they have been inserted from above, but a pair of carefully inserted 1-mm-thick brass wedges would be far from having the reliability of a good old 5-mm-thick oaken wedge smacked into place with a big hammer - not to mention that this method wouldn't provide any answer for all the tubular, single-piece collars, which are a majority.

What are we left with, then? Even renown experts and museums have given up on that quest and resorted to using a wedge on such axes.

But I have a theory to offer - and I'd love to see a blacksmith testing it in practice.

You see, there is an item in European history (until recent times), subjected to harsh stress and daily use, which managed to fix to each other the worst possible shapes in iron and wood - a cylinder around another cylinder - without the use of any wedge, nail, glue or other element. This object is the carriage wheel. To perform this miracle, the wheelwright would prepare an iron banding that would be a little bit too small for the intended wheel. This banding would then be heated in a fire, so that the heat would get the iron to expand - just enough to fit onto the wheel. The iron band would then be put into place, and quickly doused with water to cool it down and get it to shrink, thus locking it into place (and preventing the wooden wheel from catching fire).

How does that relate to our wedge-less Dane-axes and their collars? To put it simply, the idea would be to prepare the haft so that with wood only it barely fits, add the copper-alloy collar which now makes the haft too thick, heat the axe eye to expand it, insert the brass-wrapped haft into it, hammer it as deep as reasonable to form the eye of the axe tightly around it, and cool the axe-head quickly to protect the wooden haft and lock everything into place.

Several elements speak in favour of such a hot-assembly method.

First, none of the surviving axes with collars shows any sign of having been decorated with metallic inlays. Of course the statistics are limited, but the fact that the options for Dane-axe decoration were either inlay or collar would make sense if the final assembly of an axe with a collar required heating the eye of the axe, which would destroy the inlay (of course it's possible, although annoying, to do the inlaying on an already hafted axe, but in case the haft would need to be replaced the repair could then only involve a collar-less haft).

Second, copper-alloys are good heat conductors, meaning that the collar would dissipate the heat and help protecting the wood from damage when inserted into a red-hot axe eye.

Third, a commonly used tool for forging axe-heads (or rather, for finishing the details of the eye) is a drift, a slightly conical punch which is hammered into the (red hot) axe eye to give it its final shape. Using the brass-covered haft itself as a drift would therefore not be a completely exotic axe-making technique.

Oh, and speaking about glue, this is where it actually comes back! What is the best way to "glue" metal to metal? Welding or brazing or soldering (depending on the temperature and metals involved)! And it is possible (however untested to the best of my knowledge on the surviving examples) that some brazing was used, brought to heat together with the axe eye so as to fuse it to the copper-alloy collar upon cooling. So, in case any archaeo-metallurgist reads this and has access to such axes, you know what to try and analyse!

So there you have it. If you are blacksmith with experience in making Dane-axes reading this and you're willing to test this hafting method, I just want to say two things:

1) I would be delighted to see the results of your test, and have your opinion about why and how it succeeded or failed.

2) maybe don't start your sharpest axe-head, and take some safety precautions before you start swinging the thing around! Just because I like my theory doesn't mean I would trust my life to it!

Yours,

Eiríkr