What were the wings, or lugs, of the famous Norse (and Germanic, in general) winged spears (krókspjót) used for? These wings were very common, and came in a variety of shapes and size.

|

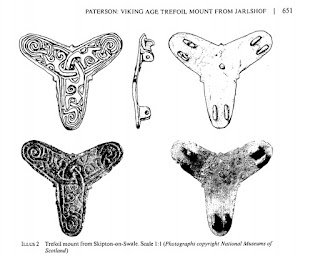

| Assortment of winged spearheads, the topmost being 38 cm long |

There are several possible answers.

The one that comes immediately to mind is that they are here to prevent over-penetration, so that the spear doesn't bury too deeply into the body of the opponent. This answer is motivated by the use of later period hunting spear (boar spear) and swords, in which the lugs or the crossbar prevented the impaled animal, sometimes as dangerous as a wounded boar, to run up the blade or the shaft towards the hunter.

This use is attested at least once, in Grettis Saga, where Gretti kills both Thorir and Ögmund with a single thrust, and the spear is buried into Thorir's body up to the wings:

IS: Í því bili kom Grettir að. Hann tvíhenti spjótið á Þóri miðjum er hann ætlaði ofan fyrir riðið svo þegar gekk í gegnum hann. Fjöðurin var bæði löng og breið á spjótinu. Ögmundur illi gekk næst Þóri og hratt honum á lagið svo allt gekk upp að krókunum. Stóð þá spjótið út um herðarnar á Þóri og svo framan í brjóstið að Ögmundi. Steyptust þeir báðir dauðir af spjótinu.

EN: Just at that moment, Grettir turned up. Using both hands, he thrust the spear at Thorir's stomach just as he was on his way down the steps, and it went straight through him. The spear was fitted with a long, thin blade; Ögmund the Evil was behind Thorir and bumped against him so that the spear pierced him right up to the wings, out between his shoulderblades and into Ögmund's chest. Both of them tumbled down dead from the spear.

However, in my opinion this use is rather the exception than the rule. Unlike the hunting spear, which is used to kill only one animal, the battle spear must be wielded against multiple opponents. Therefore, one cannot wait with an immobilized weapon until the first opponent is dead - the spear must be retrieved quickly and used again against the other incoming enemies. So spear thrusts have to be quite shallow, even more so when the spear is used one-handed: as soon as the blade encounters a bit more resistance, it must be withdrawn, or it risks getting stuck in the wound it created. This applies just as well for winged and wingless spears. Besides, wings are present on spears with various sizes of blades, including very large hewing spears where the blade is almost broader than the wings (so that the wings would get into the wound) and so long that the opponent would be pierced through long before the wings reach his body (and such an exaggeratedly deep thrust is useless, and not recommended for the aforementioned reasons).

The wings must therefore have another role. And this role is contained in the name of the weapon: the krókspjót is a "hooking spear", and the wings are called krókar, that is "hooks".

Before the Viking Age, there were even example of spearheads having literally (and laterally) hooks on the socket, not wings.

|

| Merovingian hooked spearhead, 7th century |

But hooking what, and how?

Well, several answers to that, again.

The one that is heard most often is "hooking limbs to hinder the opponent, hooking the shield to create openings". And again, it might not be the most important answer.

Just like in the case of over-penetration, one important point is to be able to retrieve the weapon quickly, since a spear is effective through its quick succession of thrusts. And to hook means to be hooked as well, therefore, hooking with the spear should be kept to a minimum, to avoid ending up with a trapped weapon and no other option than to drop it and draw an axe or a sword to keep up the fight.

In the case of a missed thrust, when drawing back the spear, an option would be to hook the limb of the opponent to unbalance him, or his shield to create an opening for the next thrust. But this might be a waste of time, compared to just withdrawing and thrusting again. Besides, if the spear is used in one hand, the shield hooking could work, but the limb hooking would be too weak to be effective.

The shape of the wings tells us something about it, too. If the goal was to harm the opponent when withdrawing the spear, the back of the wings would be sharpened - and it is never the case. If the goal was to hook anything when withdrawing the spear, the wings would have a shape optimised for hooking backwards - and it is not the case.

There are Dark-Age spearheads from Finland (of which I can find no pictures at the moment) that have the wings "backwards" compared to the Norse spears, and that could be a sign that the spear was meant to hook in a drawing motion, maybe used two-handed to create openings in a shield wall. However, the roughly triangular shape of the wings on Norse spears proves the exact opposite: the shape allows the spear to slide quite easily on encountered obstacles when it is withdrawn (remember, you don't want your spear to get stuck anywhere), but it maximizes the hooking ability during the thrust.

My interpretation is that such wings where most effective during an overarm downward thrust: the thrust intends to get in the gap between the opponent's shield and his helmet, and if the shield is raised for protection, the wing will push it out of the way and the thrust will connect anyway. At this point, it is just a hypothesis, and it will have to be tested with weapon simulators in sparring, and in a cutting session, to confirm this interpretation.

|

| The overarm guard on the Bayeux tapestry |

And remember, in Oðinn we trust, and with spears, we thrust. ;-)

Yours, Eiríkr