|  |

| Ugh. | URGH! |

I really HATE lamellar armour. Or rather, I hate the stupendous amounts of lamellar armour seen in viking reenactment, and especially its horrible leather variant.

But I'm willing to talk about my problems in order to feel better about them, so let's have a go at lamellar armour and leather armour.

But I'm willing to talk about my problems in order to feel better about them, so let's have a go at lamellar armour and leather armour.

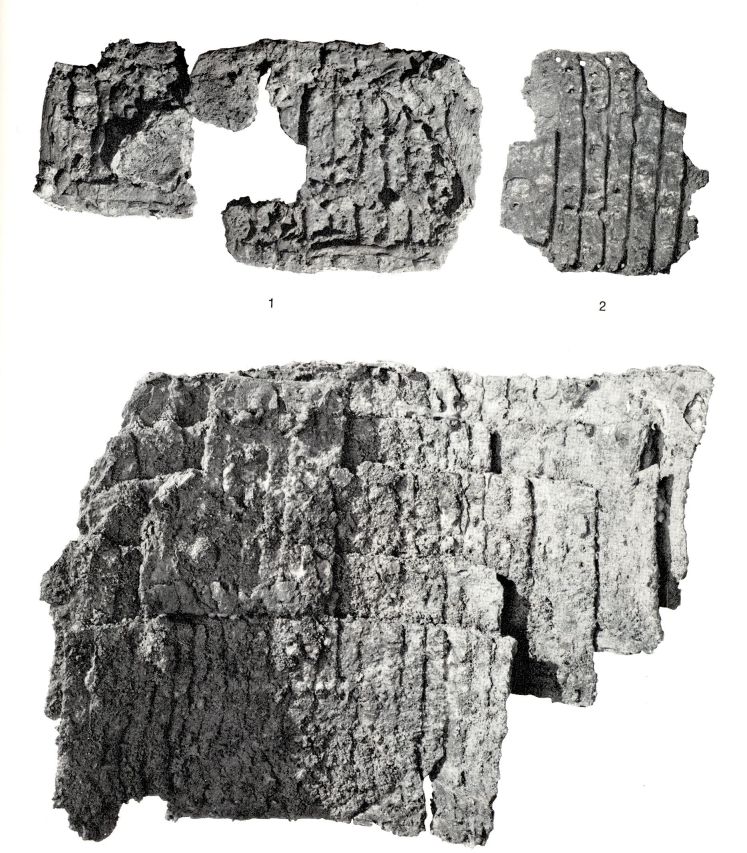

| Set of plates from a lamellar armour found in Birka (now kept in Stockholm History Museum) |

In Old Norse, lamellar armour was called "spangabrynja". "Brynja" is the byrnie, or mail shirt, while "spǫng" designates a spangle, a floe or ice flake. So a "spǫng" is a small, flat, shiny thing, and it is perfectly logical to think of the "spangabrynja" as a spangle, i.e. lamellar, armour. However, this kind of armour is mentioned extremely rarely, appearing only in chapter 63 of the Laxdœla Saga, and in chapter 10 of the Sagan af Hákoni herðibreið, in the 3rd book of the Heimskringla. So seeing them everywhere in all reenactment battlefields does not seem to reflect the realities of the Viking Age.

Now that we know for a fact that these lamellar armours did exist, both practically and conceptually, we'll see where they did come from, and how they did look like.

For the origin, the answer is twofold.

The first possible origin for lamellar armour is local: it might be a descendant of the types of armour found either during the Vendel Age, or more generally in North-western Europe during the Migration Era.

An example of Vendel splint armour from Valsgärde is discussed here in details (only in Czech).

|

| Valsgärde splint armour, 7th century. The interpretation of this armour is debatable, more recent studies see these sets of staves as shin and forearm protections. |

An example of earlier Germano-Roman lamellar armour is discussed here in details (only in Czech, again...)

|

| Fragment of 5th century Germano-Roman lamellar armour. |

It is interesting to note that the Valsgärde armour seriously lacks longitudinal mobility, while the Roman lorica segmentata lacked transversal mobility - the Germano-Roman lamellar armour solves the two problems.

The second origin of the Norse lamellar armour is obviously Varanguian. Lamellar armour is well known to have been favoured by Byzantine military, and the elite Varanguian guards, of Norse origin, loved using the heaviest available protection, therefore wearing lamellar armour on top of mail. Many Varanguians, such as the future king Harald Hardrada, came back to Scandinavia after their service in Byzantium, and they could have brought back with them such armour, or at least the idea of it.

Therefore, the Viking Age "spangles" that we find in museums today come from armour that either derived from earlier Scandinavian designs, or was imported from Constantinople, or was a copy of these imports.

The looks of such sets of lamellar armour it unknown, too. What everyone is mostly used to are the lamellar armours with smaller or larger pauldrons and faulds, that we see in reenactment (or on the first to pictures of this page). But my bet is that they most probably looked like this:

|

| Byzantine fresco showing 12th century lamellar armour |

Well, maybe the pteruges were not part of the Scandinavian lamellars, but the armour itself is nothing but a cuirass, while the protection of other parts of the body, such as the arms or the hips and thighs, is granted by something else, lighter and more mobile, such as mail or pteruges.

The reason behind the shape of the reenactment lamellars is the wish of the fighters of having more and more protection to bash each other with more and more force on a set of allowed targets, which include the torso, the thighs and upper arms. Therefore, sacrificing mobility for the sake of protection in a context were the number of moves is reduced by the fighting rules makes sense.

On the other hand, real armour is always a trade-off between weight, mobility, and protection. Historically, one can see that most rigid or semi-rigid torso protections stop at the waist, not at the hips or below, to allow for a full flexibility of the body. The shoulder protections have to be mobile as well, and are therefore highly articulated, unlike the broad single-piece pauldrons that we see on the first two pictures.

The need for flexibility of the lamellar armour is further illustrated by an element that we can see on the archaeological finds, but never on modern reconstructions: the plates are of many different types and sizes. We see larger scales on the chest and stomach, to provide a more rigid protection to vital areas, and smaller plates that allow for more flexibility around the shoulders.

Now, on to leather armour!

|  |  |

| Game nr. 2: | ||

| Which of these leather armours has the slightest chance of being historically accurate? | ||

You can be level 0 and think that leather armour did exist. Or be level 1, and know that it didn't. Or level 2 and know that it actually did exist, but not in the form of that weird leather plate armour we often see in fantasy settings. Let me take you to level 3...

Leather can obviously be a very resistant material. Be it very thick veg-tanned leather or "boiled leather" (i.e. leather cooked in wax or gelatine), it can provide a substantial protection against cuts and thrusts. As late as in the 17th century, thick leather was used as a primary level of protection again edged weapons. The word "cuirass" itself, which designates an armour for the torso, comes from the French "cuir" - leather.

Now, how was it in the Viking Age ?

We know that Norsemen used mail for protection, which is highly ineffective at absorbing impact. Therefore, the use of gambesons or other kind of subarmalis is very likely, even though unattested. Leather, either in one thick layer for a subarmalis, or as the outer layers of a padded gambeson, is a good material, and there comes a first possibility of having some kind of leather armour.

What about leather lamellar armour then? Well, as we have seen, lamellar armour was already very rare, and the chances of having some leather surviving archaeologically were close to zero. And having someone making a copy of an elite armour in a cheaper material is not impossible, but rather unlikely.

But what do the texts say about this? Well, here comes the much-dreaded word : "leðrpanzari"! It exists! A leather panzer, it must be some kind of leather armour! Well, not quite. Translators rather use the term of "leather jack" - so rather a gambeson - and we'll see that it is for good reasons.

The word "leðrpanzari" appears only in one text, the Karlamagnús saga. It is a Norse translation of the "Matter of France", a collection of Carolingian chansons de geste, for the court of Norway. So we're not strictly speaking looking at a text that is supposed to describe Norse arms and armour - the Matter of France is even said to have Oriental influences, which can be seen for example in the pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

In this saga, the word "panzari" appears 23 times. This word comes from the Latin "pantex" (belly, intestine), through the Frankish "pancier", which designates a cuirass (no leather pun intended). So we're dealing with a kind of armour for the torso.

It is interesting to note that the world "brynja" (mail shirt) appears over a hundred times, which shows how unimportant the "panzari" is.

Out of 23 times, the "panzari" is described:

- 7 times as a "leðrpanzari"

- 2 times as a "silkipanzari"

- 1 time as a "linpanzari"

Do I even need to translate these words or do you already understand that there is no way that "panzari" would designate a lamellar armour? Would you believe in plates made of linen or silk? No! The "panzari" is most obviously a kind of gambeson, which can be made of a variety of materials, depending on the wealth and the wishes of the wearer.

Silk-covered gambesons became quite popular among nobility in Europe from the 14th century on, but we can imagine Easterners wearing such kind of protection in the tales of pilgrimages to Jerusalem and other travels to the Middle-East.

So, I guess we're done here. As far as Norsemen are concerned, they probably wore a "panzari", which could be made of leather, and, if they could afford it, a "brynja" over it. If they wished and had the extra silver, they could also have a "spangabrynja" on top of the "brynja". Maybe (maybe) someday I'll come accross a clever reenactor in a perfectly historically valid kit, with a short lamellar cuirass made of a variety of specialized plates... I'll take pictures, I promise.

Yours, Eiríkr

UPDATE!

Another point about the "spangabrynja" that I think is worth mentioning: by the time the sagas were written, lamellar armour was clearly obsolete, but coats of plates were starting to appear in Europe. And guess how they were sometimes called? "Plate hauberk" (watch the whole video, it's worth it).

So, did the word "spangabrynja" used by the authors of sagas designate the Norse or the medieval armour? That's an open question.

UPDATE!

A few new thoughts about the "panzari":

According to several sources, like Hjalmar Falk's Altnordisches Waffenkunde, the "panzari", or linen gambeson, only showed up in Scandinavia aroud the 12th century, when the so-called Viking Age was long over, and Scandinavian kingdoms where fully integrated into the European culture, sharing a common faith and technology.

So it seems that the "panzari", be it made of leather, linen or silk, would be anachronistic for Norsemen. However, some kind of arming garment but have been worn under mail armour to provide some padding. It is maybe what the word "vapntreyja" (arming jacket / jerkin) refers to. It occurs often that the "vapntreyja" is mentionned as being "ermlauss" (sleeveless). This reminds of the Roman subarmalis, which was a sleeveless jacket with pteruges worn under the lorica hamata (mail armour). The subarmalis was either thick leather, or linen, or lighter leather padded with wool and / or linen... We don't really know, even for the Romans who wrote plenty. Guessing what Norse arming garments could have looked like it even more tricky. But experimenting with leather, wool and linen on Scandinavian pattern with or without sleeves seems a good starting point.

UPDATE!

Another point about the "spangabrynja" that I think is worth mentioning: by the time the sagas were written, lamellar armour was clearly obsolete, but coats of plates were starting to appear in Europe. And guess how they were sometimes called? "Plate hauberk" (watch the whole video, it's worth it).

So, did the word "spangabrynja" used by the authors of sagas designate the Norse or the medieval armour? That's an open question.

UPDATE!

A few new thoughts about the "panzari":

According to several sources, like Hjalmar Falk's Altnordisches Waffenkunde, the "panzari", or linen gambeson, only showed up in Scandinavia aroud the 12th century, when the so-called Viking Age was long over, and Scandinavian kingdoms where fully integrated into the European culture, sharing a common faith and technology.

So it seems that the "panzari", be it made of leather, linen or silk, would be anachronistic for Norsemen. However, some kind of arming garment but have been worn under mail armour to provide some padding. It is maybe what the word "vapntreyja" (arming jacket / jerkin) refers to. It occurs often that the "vapntreyja" is mentionned as being "ermlauss" (sleeveless). This reminds of the Roman subarmalis, which was a sleeveless jacket with pteruges worn under the lorica hamata (mail armour). The subarmalis was either thick leather, or linen, or lighter leather padded with wool and / or linen... We don't really know, even for the Romans who wrote plenty. Guessing what Norse arming garments could have looked like it even more tricky. But experimenting with leather, wool and linen on Scandinavian pattern with or without sleeves seems a good starting point.

No comments:

Post a Comment