This first post will not exactly help you to dye clothes in red. Not directly. It aims at helping you gain awareness of why it's actually not so easy to build certainties while dealing with accurate, archaeology-based reenactment.

I had to make this post, because doing reenactment is really a matter of how deep you are willing to delve, how much you are willing to read... and where you will choose to stop.

The better I get, the more uncertainties I have to face concerning the "accuracy" of what I'm doing.

"I am a dwarf and I'm digging a hole", or how deep reenactment takes you (not necessarily underground)

Let's start with a few facts. When making costumes, we base ourselves on archaeological finds.

Firts obvious statement : what we have been able to recover from the past is extremely little. Concerning viking age, we have maybe a dozen of extent garments, and they are not all coming from Scandinavia. Is a dozen garments representative from a period of history that lasted something like 300 years ?

Certainly not.

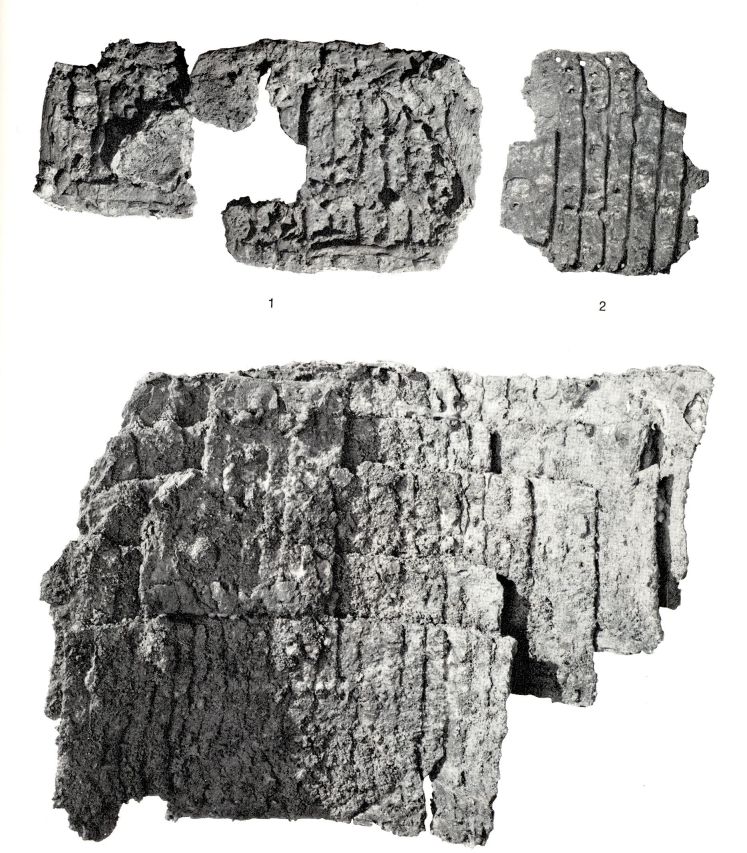

Second (a little bit less obvious) statement : fabric rots. The fragments that we have recovered were preserved by special conditions, whether mineralized in contact with metal (from brooches, knives, swords, shield bosses, silver and gold thread from table-woven trims, silver and gold posaments, pins, pendants, etc.) or preserved by particular qualities of the soil (for example, in bogs, like Huldremose "peplos-dress" which is not from viking period).

|

| Tablet-woven trim from the Kostrup suspended dress photo by Hilde Thunem taken in Odense museum, Denmark |

Some fabric have been recovered in funny circumstances, for example, Haithabu's (modern Hedeby, Germany) viking-age harbour yielded fabric that had been used to repair ships, that had been doused in tar.

That leads us to the third (not obvious at all) statement : you have to be very careful when using evidence to back your costume projets. If you base yourself on evidence recovered from a grave, most likely, that means mineralized fabric in contact with metal. And if there is metal, most likely, that means a wealthy grave. Check if the assessed level of wealth of the grave matches your character's level of wealth.

Ship-burials are for very wealthy people. Oseberg's lady was a queen, or a chieftain's lady. That means that despite the fact that we are very happy to have plenty of evidence from her grave, maybe, you shouldn't use that for your costume. Tablet-woven trims were luxury items, if there are gold and silver threads to preserve them, you will need all of your costume to be accordingly rich.

| |

NOT a middle-class garment, so if you are, choose something else.

Dress made by Toril Sørbøe Rojahn, posted on Viking Clothing Facebok group |

Some of the fabric recovered from excavations are more likely to have belonged to humble people. The clothes from bodies found in bogs, the fabric from Haithabu harbour are probably better evidence if your character is humble. But it's not easy to make out their colour !

The acidic Ph of the bogs makes it difficult to analyze the dyes. It's the same for clothes that have spent a long time in the sea, or under ice (the Greenland settlements have yielded a lot of extent garments, although they are XIIIth-XIVth century, not viking-age).

The conclusion is : the coloured clothes samples that are at our disposal to guess what was used for dyeing are not representative of "the viking period". They can be representative of the settlement, or of the burial site, though. In Birka, there was a wealthy area of burials, and a poorer one. Guess what ? More grave goods are recovered from the wealthy area. Solid information about a specific site doesn't allow us to jump to general conclusions.

Most costumes we see in festivals are typical of high-rank individuals. There are trims and jewels galore. Do not let this lead you to the conclusion that most people of the viking period dressed this way !

In Thor Ewing's opinion, red clothes were more likely to be costly items, the dyed fabric either being imported, or dyed with imported madder.

Can we be sure of that ? No. We can only gather evidence, and make educated guesses.

In my opinion, fabric produced domestically could not have only been dyed with the top-quality, most-efficient dyestuffs. Some must have been dyed with local plants. But this would have been done by poorer individuals... and unfortunately, we don't have a lot of evidence for them, because their graves have been lost.

|

| Red dyes achieved with bedstraw, by Jenny Dean |

Moreover, when dyes can actually be analyzed, they are not always recognized. Quite a lot of yellow samples from the viking age haven't been identified at all. They are refered as "X yellow". Dyer's broom and weld are quite commun yellow dyes, but they are not the only ones. A considerable number of plant gives yellow, and many of them are solid dyes that would not be sneezed at by the housewhife when she made her cloth.

A smaller number of plants gives really interesting red colour, which (thankfully !) restrains the field of investigation, but still there is a lot of space for study.

I intend to research evidence for red dyes and their use during the viking period, and write an article on the subject. But it's a tricky subject indeed, and we have to speculate, guess, and make hypothesis.

I hope this preliminary article have "rung your bell" and made you more aware of the need for carefulness when embarking on making a costume, choosing the fabric, the weave, the colour and the ornaments.

See you (hopefully) soon for the "study in scarlet" article itself !

Aelfgyva